From May 17, 2023 to June 30, 2023

Galerie Tanit, Munich, Germany

Abed Al Kadiri, Antiquities 2: My Mother's Hand, 2023, Bronze, 17 cm x 12 cm x 22 cm, Edition 1 of 3

" the artist would spend hours at his mother’s feet, under her sewing machine, with only paper and pencils as his companions "

Under the Sewing Machine is Abed Al Kadiri’s exhibition at Galerie Tanit and a continuation of his ongoing autobiographical project The Story of the Rubber Tree (2016–).

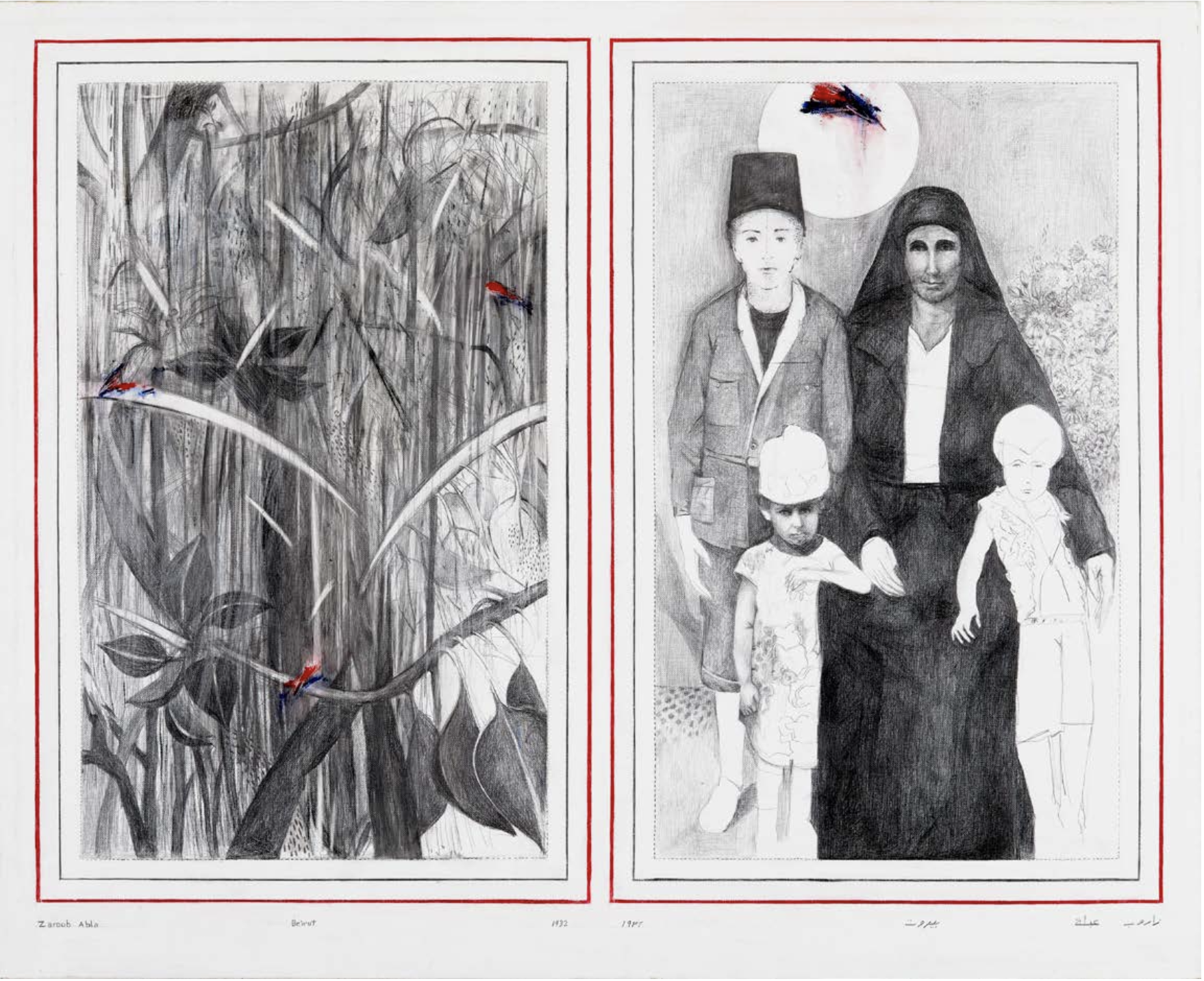

Both a reflection on the fragility of family and an unguarded investigation of the self, Under the Sewing Machine largely reckons with a single image: the only existing photograph that captures the artist’s immediate family together, standing in the rubble of their charred home during the Lebanese civil war, his father’s spotless gendarmerie hat plainly visible and his seamstress mother’s sewing machine a shadowy remnant. A family portrait of crisis, vulnerability, and surrender, the backdrop for the latest instalment of this narrative is the cacophony of the raging conflict in Lebanon and the internal turmoil of domestic violence in the artist’s own home. The photo appeared in his life only recently—part of his late father’s possessions—just months after Under the Sewing Machine was initiated.

The artist’s mother, a professional seamstress and tailor—seen in the photo with her five children, all of whom face the camera except the toddler-aged artist—boldly challenged the patriarchal norms of her conservative community and family of nine brothers. Rejecting societal expectations, she not only fought to protect the foundations of the family but gained financial independence from a domineering husband who was fifty-five years old when Al Kadiri was born, and who appears standing alone in the photo, withdrawn from his family.

That family photograph became the catalyst that repositioned Al Kadiri’s reading of his personal history. It plays on a marked duality between two wars: the political battles on the streets and a tyrannical father at home—both ruinous at different scales. This rare, yet revealing, family portrait became a bridge to the artist’s repressed trauma and the damage inflicted upon the family which lead each of them to a certain destiny, impacting the dynamic within the family itself. Seeing himself as a young child reaching, seeking, into the white space, Al Kadiri describes the photograph as ticket to time-travel. It also helped Al Kadiri make a connection between what had become a medium of choice over time—charcoal—and the burning of his home. He frequently uses archival photographs of his family as a starting point for a multidisciplinary body of work that excavates the layers of trauma that have affected the artist deeply into adulthood, including the revelation that he was an “unwanted” child, alive despite forced abortion attempts.

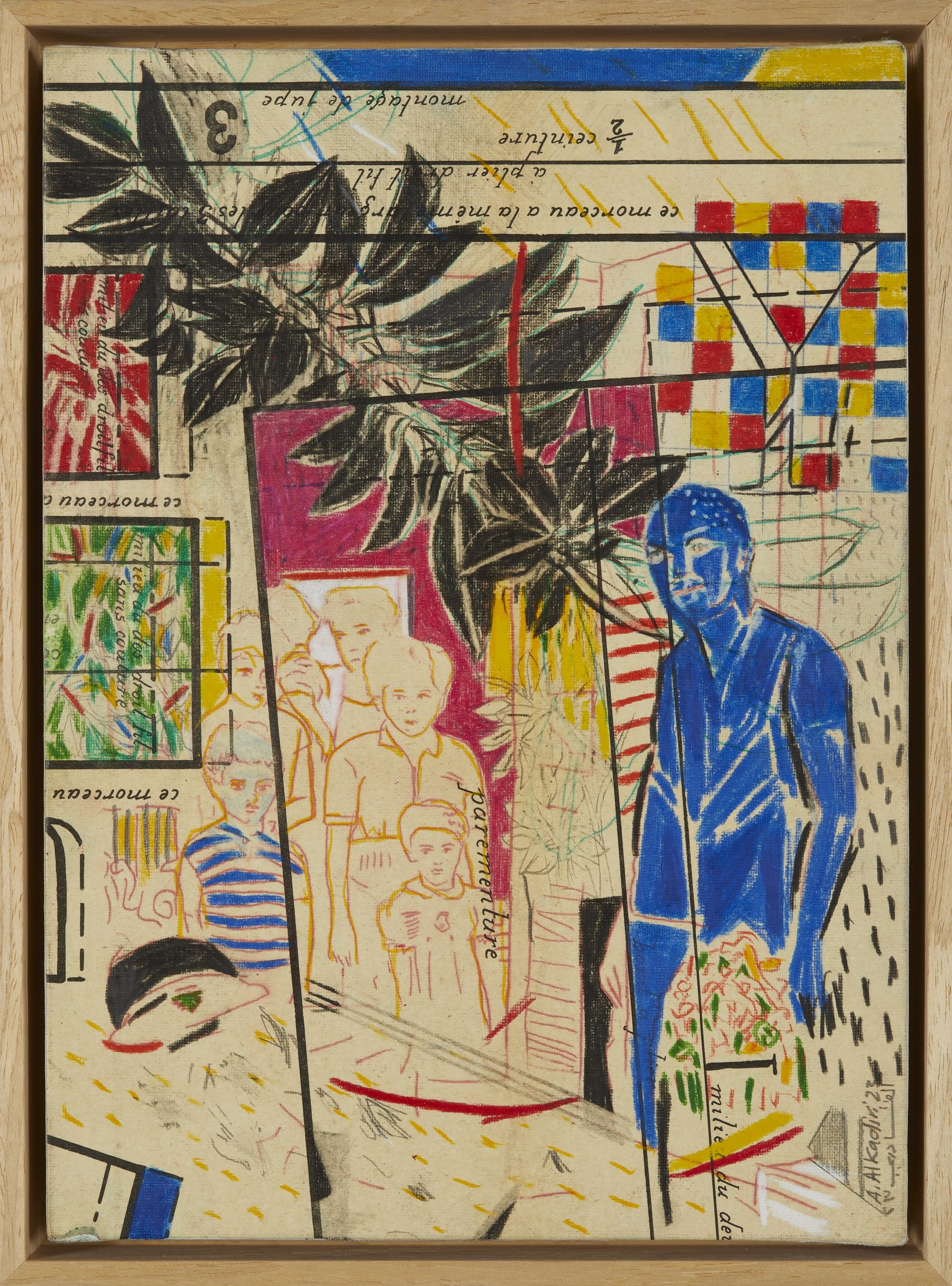

The exhibition draws on a distinct childhood memory of his uncle’s textile factory, where the artist would spend hours at his mother’s feet, under her sewing machine, with only paper and pencils as his companions—a refuge encircled by soft walls of fabric. Leaning heavily on the artist’s childhood tools: crayons, colored pencils, and the sewing pattern paper familiar to him from those days at the factory, Al Kadiri gives this moment in time new life and voice by allowing it to narrate his family’s painful fissure. Thus the arc of this body of work shifted—from a nostalgic, romantic image of a child painting under a sewing machine to a crystallization of memories and trauma.

A suite of ten etchings was the basis for an artist’s book created during the COVID-19 pandemic—a time during which a more autobiographical approach began to appear in Al Kadiri’s work. About the book Venetia Porter wrote: Titled My Father’s Grave, the book begins with an old family photograph taken in about 1932, that Abed Al Kadiri found by chance among his late father’s possessions. It shows his father—a boy of two or three—with his siblings and grandmother. Portrayed in different ways across the fold-out pages of the book, in one drawing the small child is now the artist himself, facing his father on his deathbed. The broken-up Arabic text is composed of the words: “One day I will visit my father’s grave. It will be like it used to be when he was alive. We won’t exchange a single word.” An intimate video installation captures the artist’s mother in her workspace today. Much of it is recorded from the artist’s perspective as a child—under the sewing machine—and she speaks candidly about the specific tragic moments in the artist’s life, illuminating her steadfastness in a sea of patriarchy. Two sculptural works embody the proximity she and Al Kadiri shared. The exhibition ends with a pencil drawing by the artist’s son based on a photograph of his grandfather as a younger man, standing beside a tank.

Weaving through key events and powerful emotions—abuse, a life-changing accident, a home destroyed, a splintered family, and a strong-willed mother—Al Kadiri has reimmersed himself in his past raising questions not only around masculinity, patriarchy, feminism, and the relationship between those notions through the lens of his working mother but creating both a sensitive homage to her and a blueprint for shedding light on intergenerational trauma.

Artists

Image Gallery

Abed Al Kadiri

Zaroub Abla

2023

Charcoal and Pencil on Canvas

130 cm x 160 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

Under the Sewing Machine

Exhibition View

Abed Al Kadiri

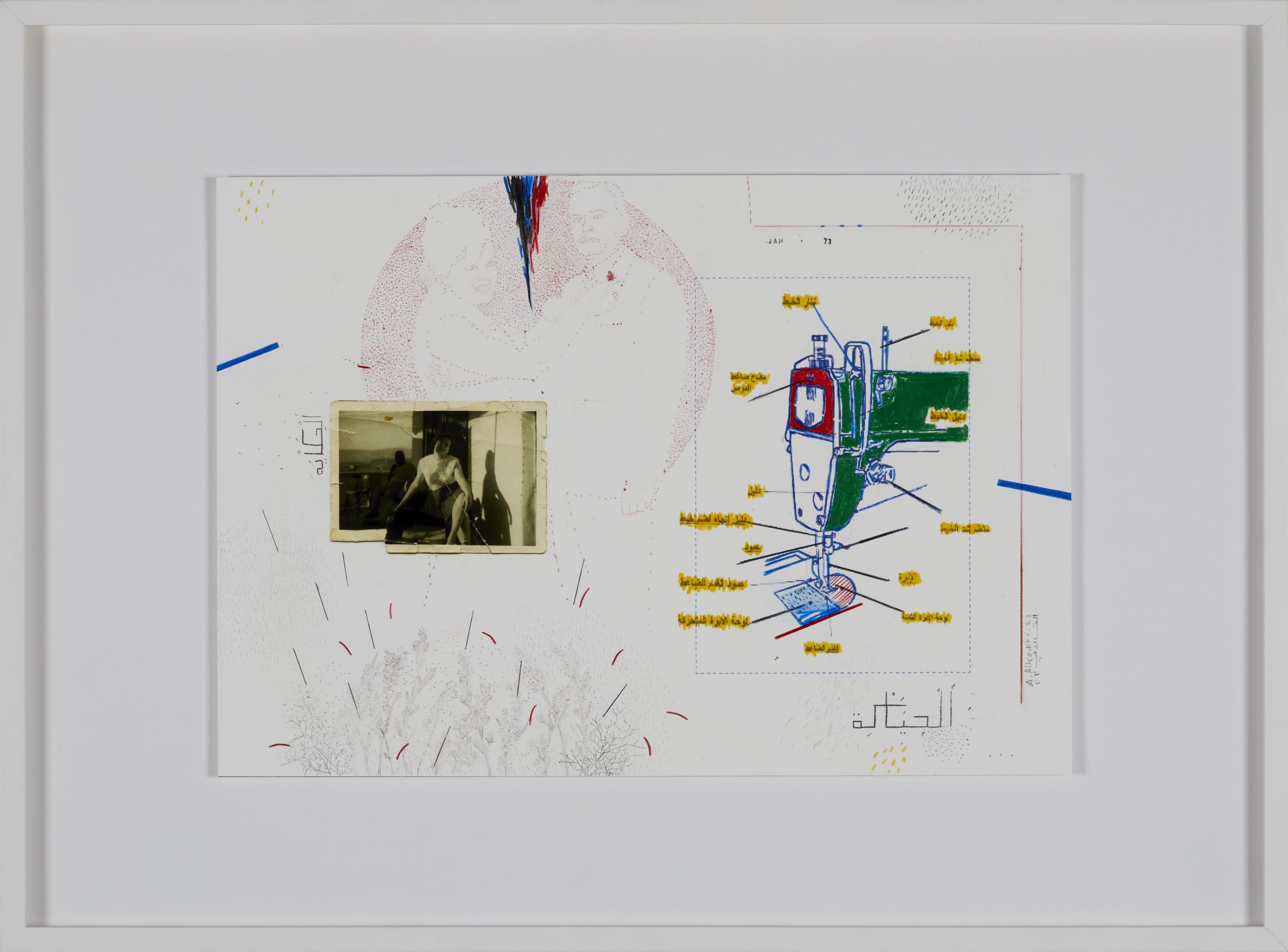

Al Hikaya Al Hiyaka 1

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

30 cm x 50 cm / 56 cm x 75.5 cm (framed)

Abed Al Kadiri

Under the Sewing Machine

Exhibition View

Abed Al Kadiri

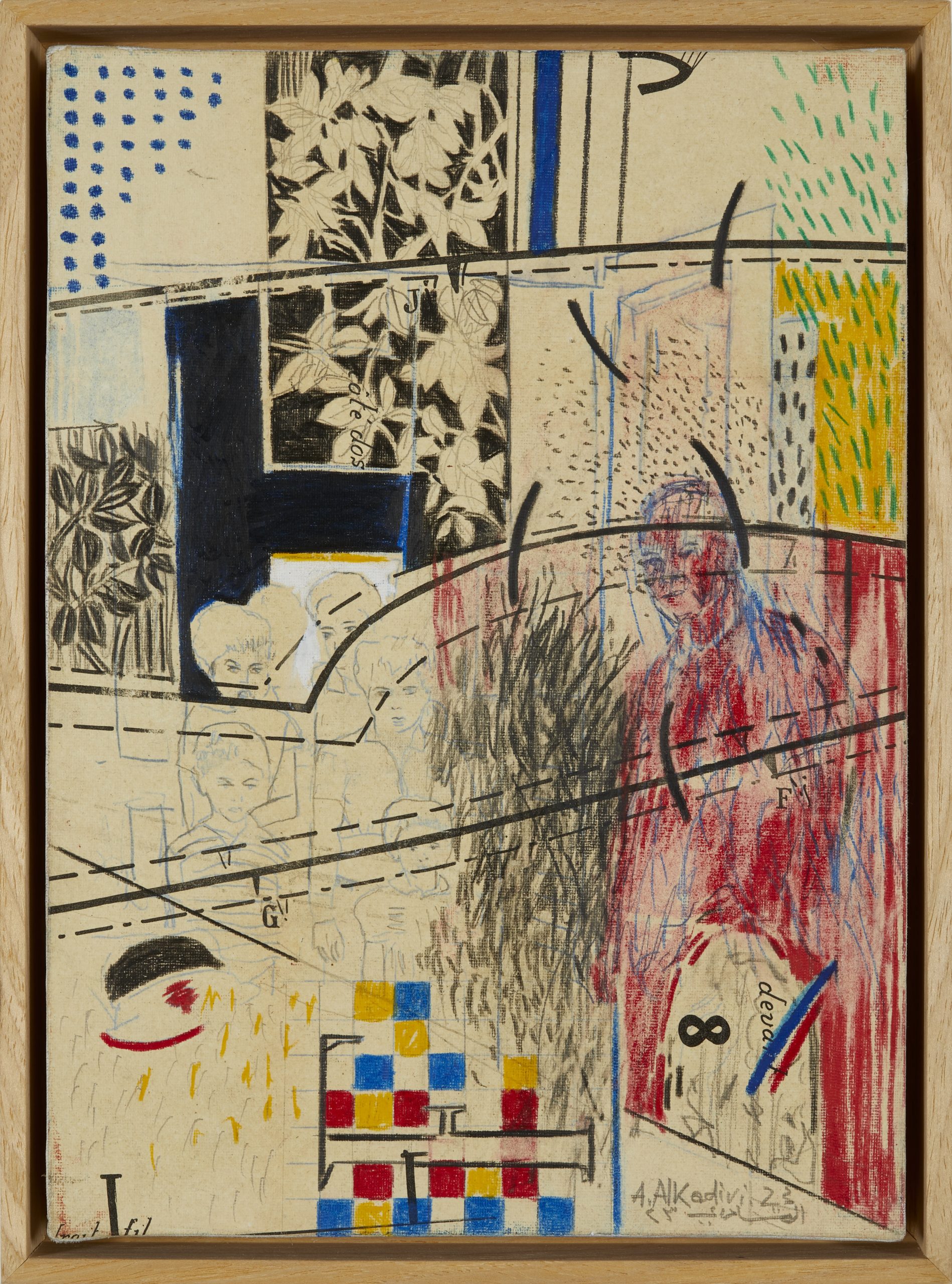

F

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

33.5 cm x 24 cm / 36 cm x 27 cm (framed)

Abed Al Kadiri

Under the Sewing Machine

Exhibition View

Abed Al Kadiri

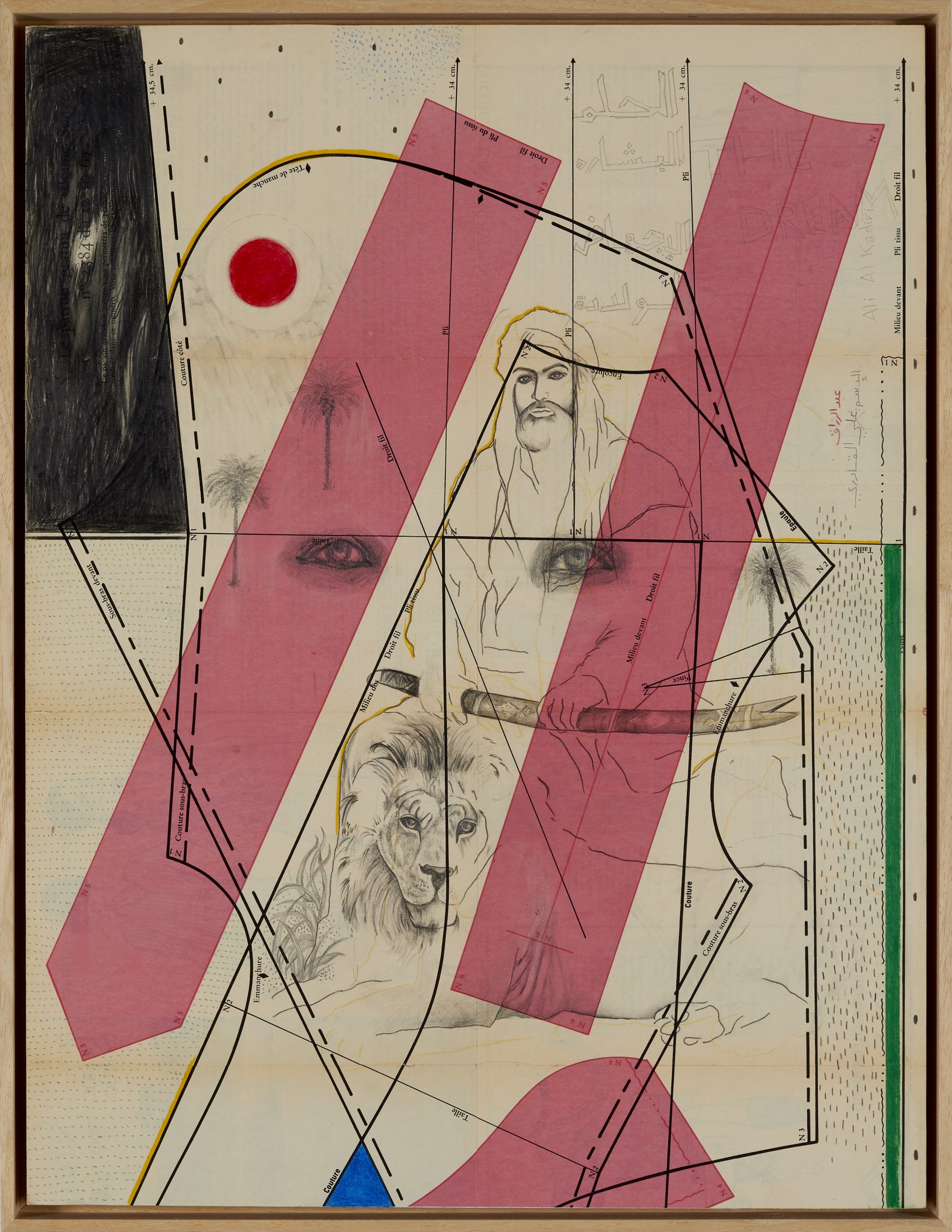

The Dream

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

64 cm x 49 cm / 67 cm x 52 cm (framed)

Abed Al Kadiri

Under the Sewing Machine

Exhibition View

Abed Al Kadiri

Fire 1985/Brother

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

73 cm x 53 cm / 86 cm x 66.5 cm (framed)

Abed Al Kadiri

Antiquities 1: My Mother's Foot

2023

Bronze

15 cm x 11 cm x 29 cm

Edition 2 of 3

Abed Al Kadiri

Al Hikaya Al Hiyaka 2

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

30 cm x 50 cm / 56 cm x 75.5 cm (framed)

Abed Al Kadiri

Y

2023

Mixed Media on Paper

33.5 cm x 24 cm / 36 cm x 27 cm (framed)

Subscribe to our newsletter for ongoing updates on our artists and exhibitions