September 1, 2021 to September 12, 2021

Gallery 12, Cromwell Place London, England

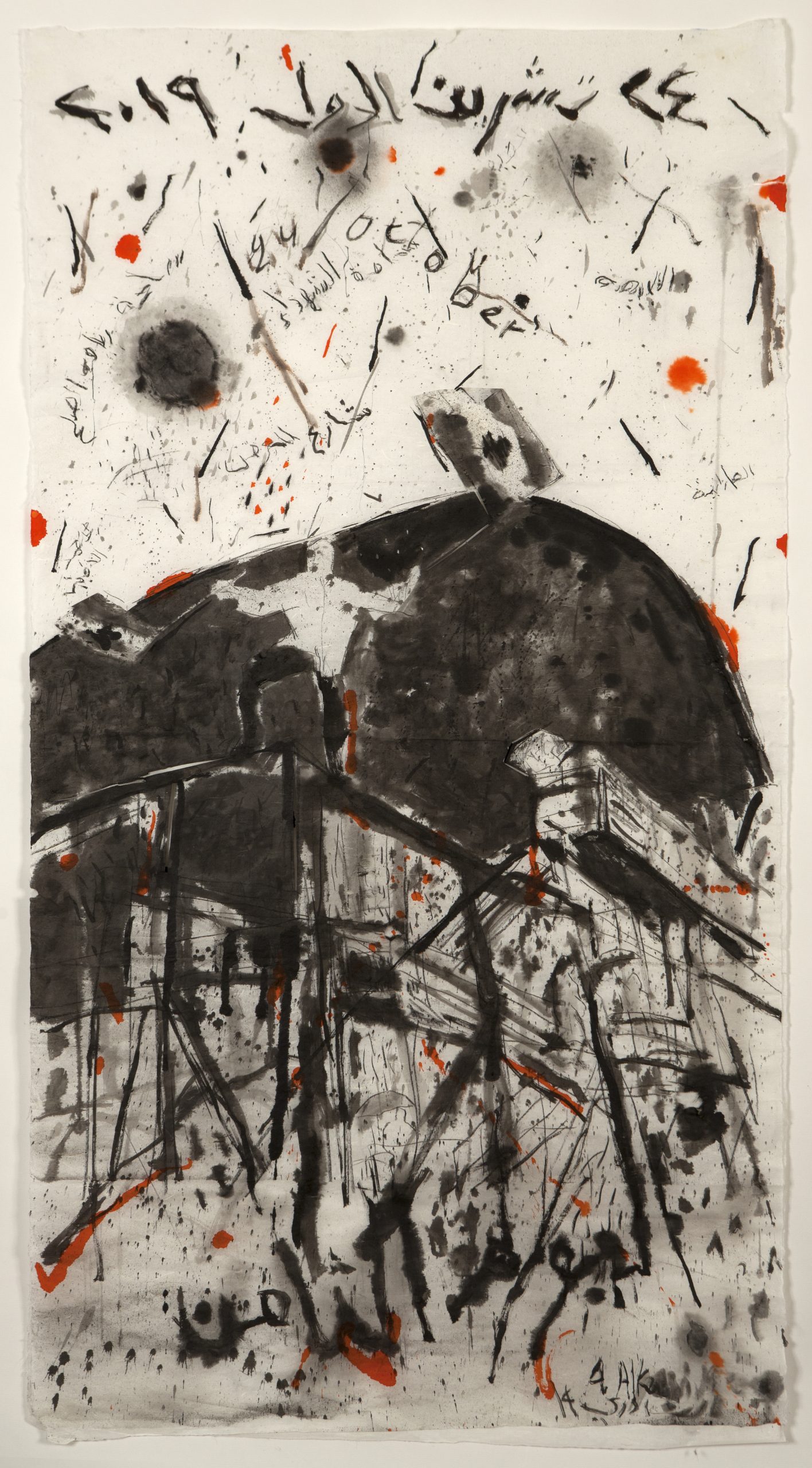

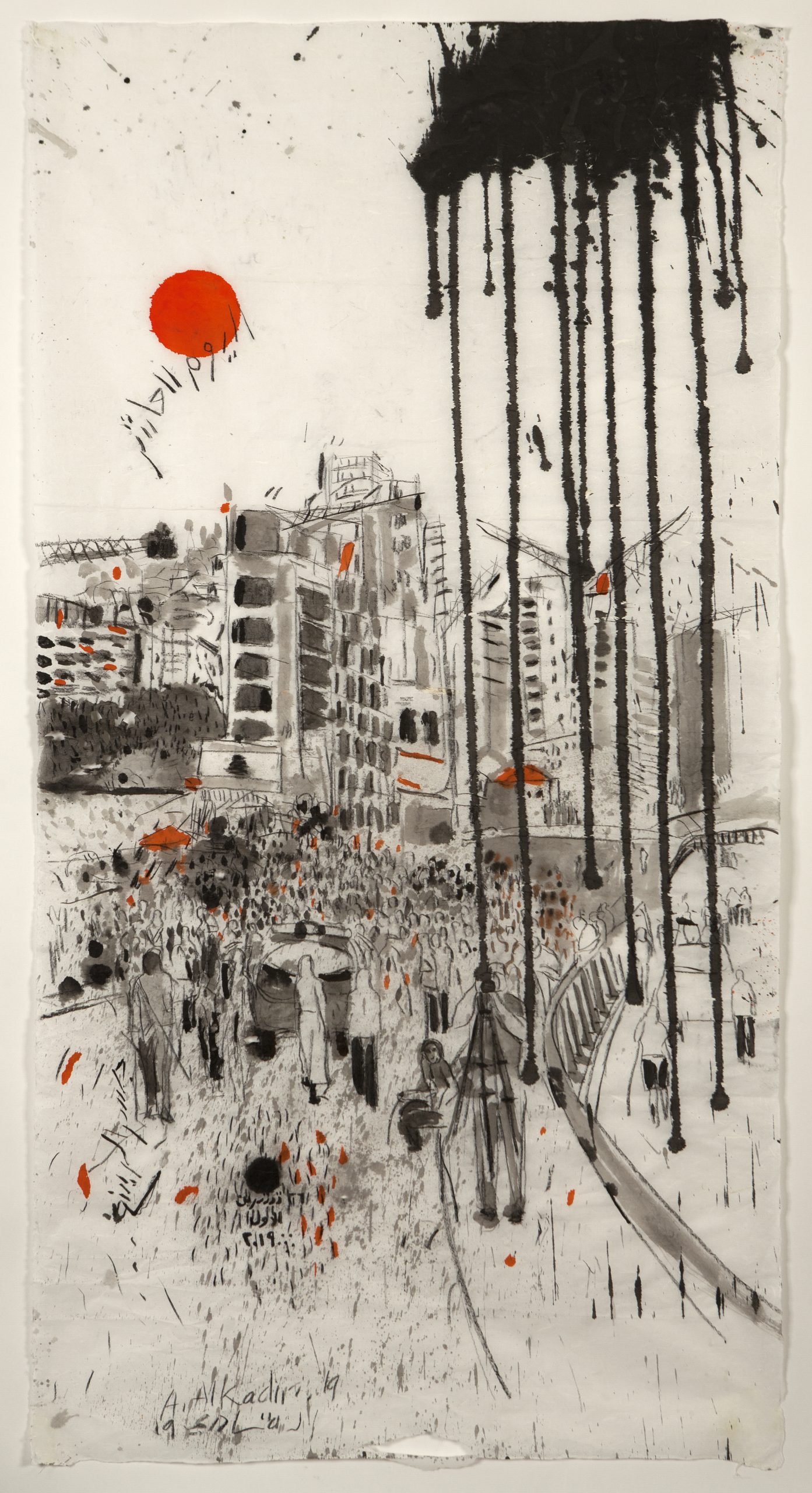

Abed Al Kadiri, October 31, 2019, 2019, Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper, 175 cm x 95 cm.

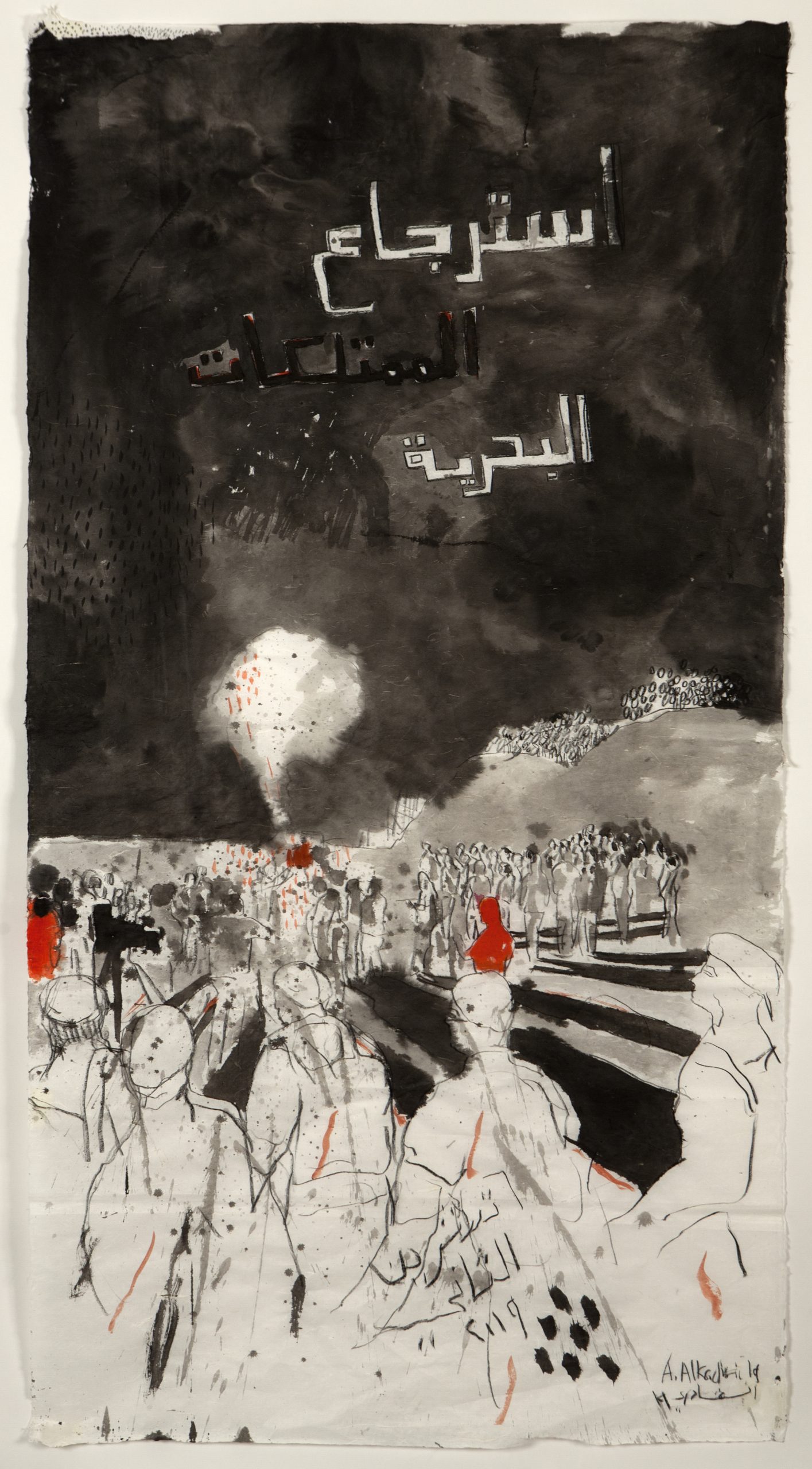

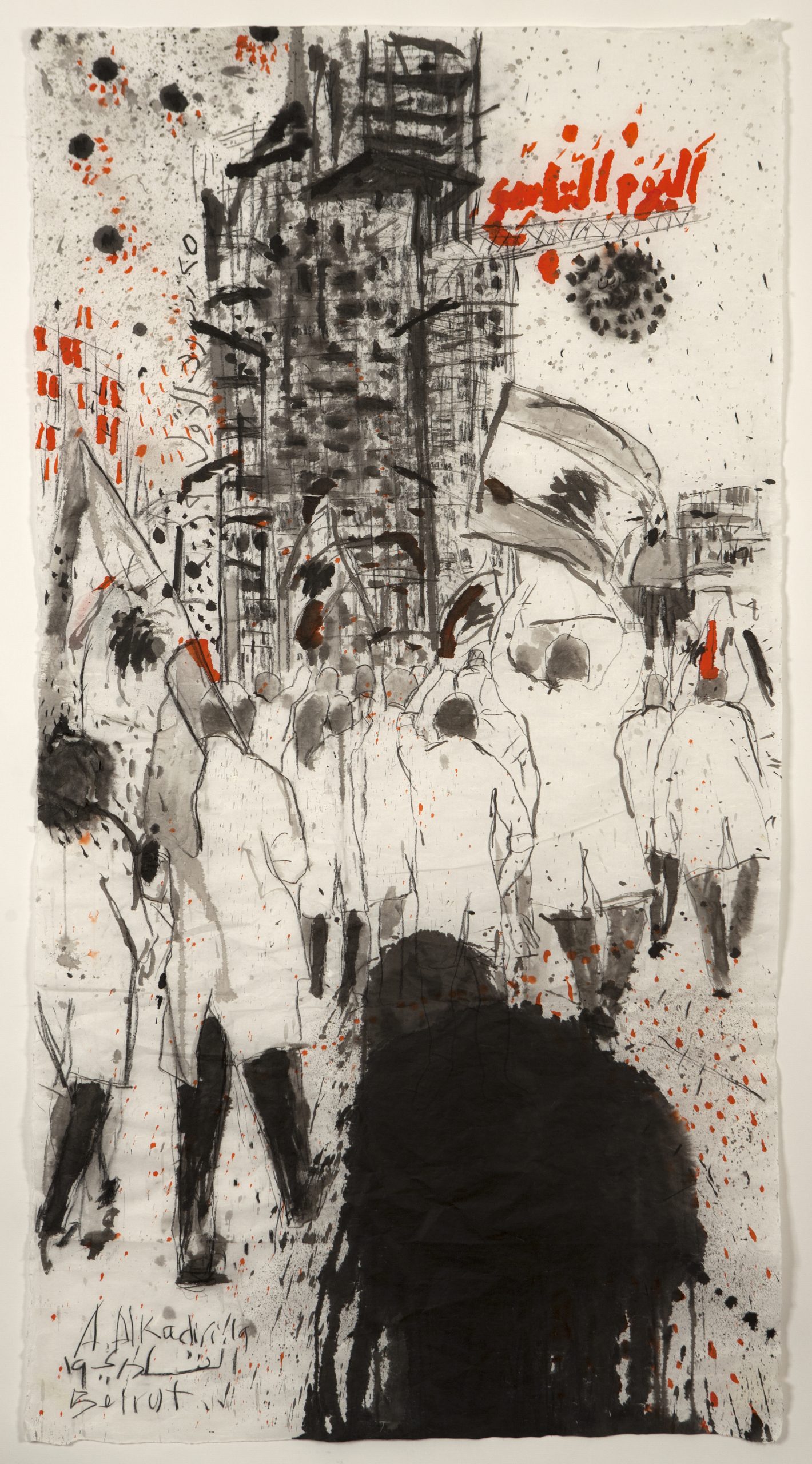

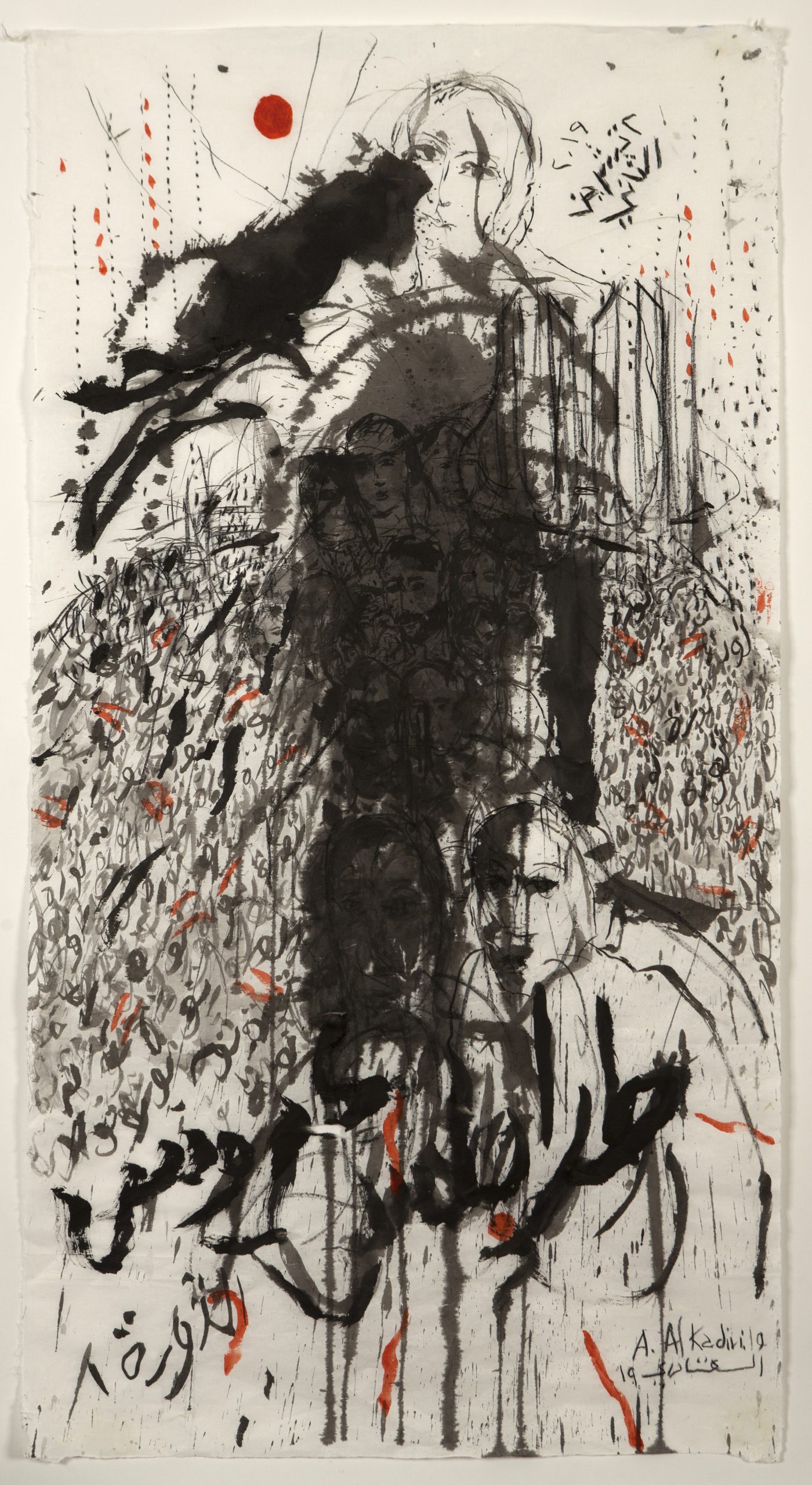

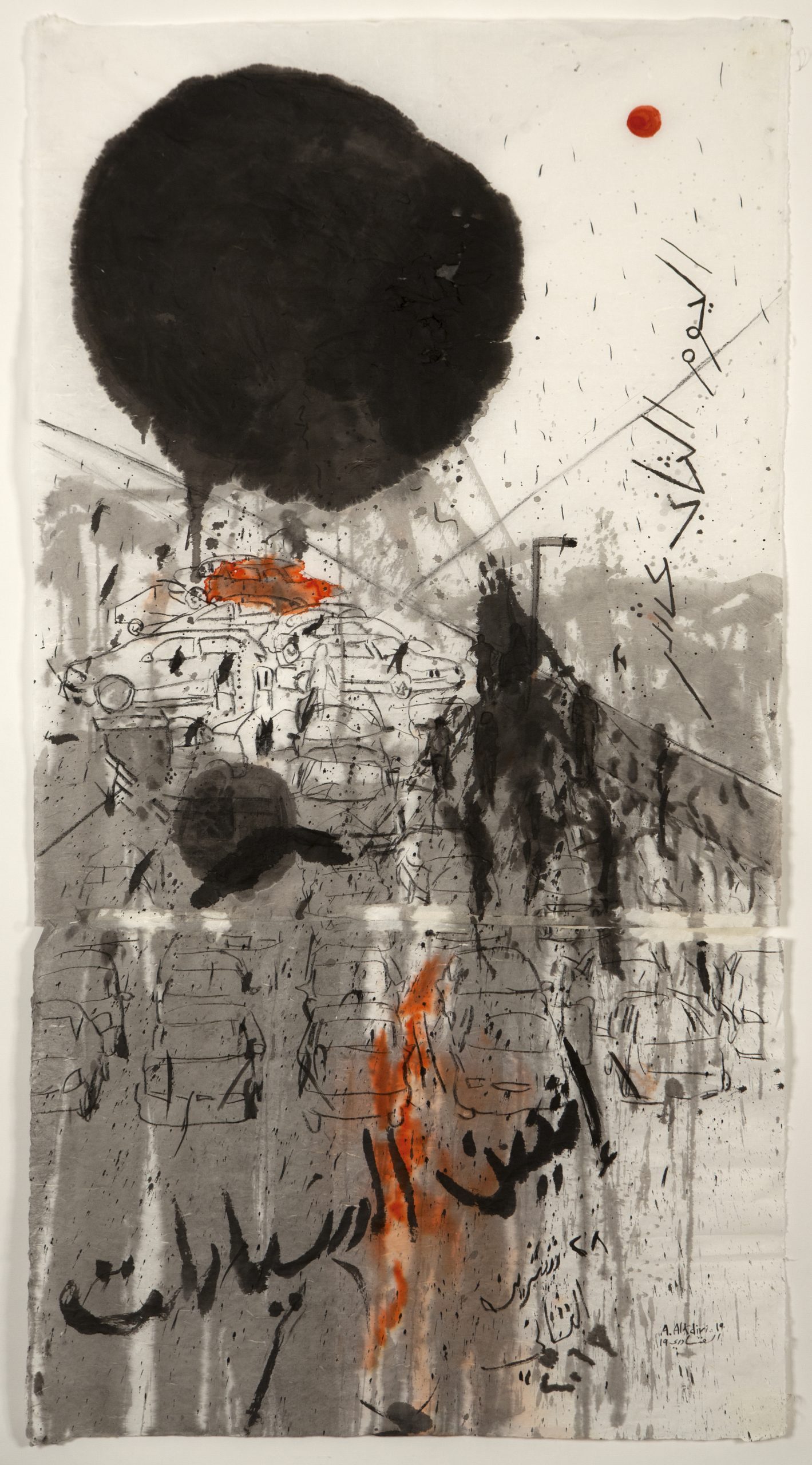

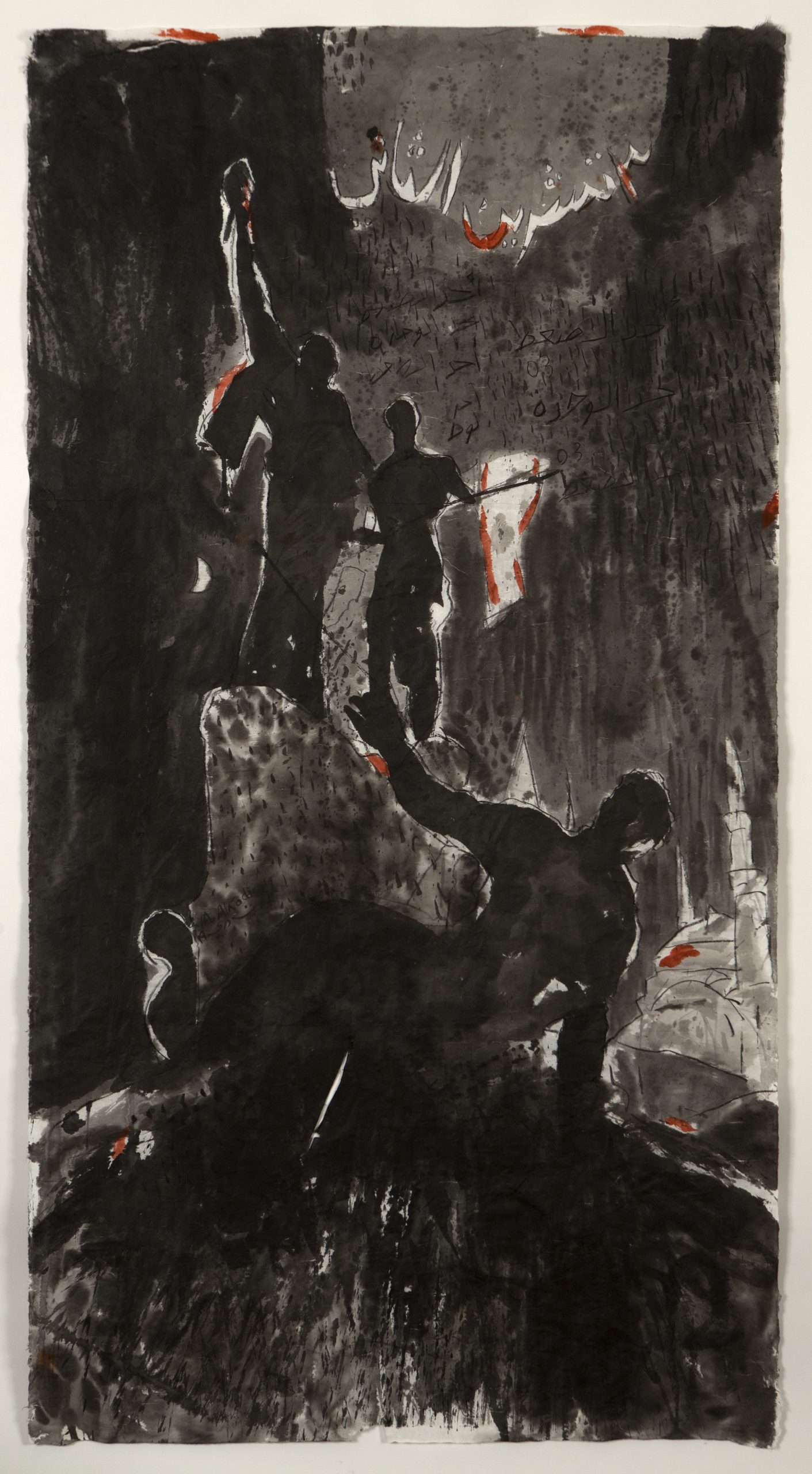

Al Kadiri’s works are a snapshot of the dramatic scenes he observed, from the crowds of protestors and clutches of flags, to menacing, dark figures set in Beirut’s looming cityscape. Drawn hurriedly in black ink onto rolls of rice paper, they show the urgency and intensity that lived in those sleepless days and nights. Each drawing has a date and a specific location; a mapping of Al Kadiri’s movements across specific places in Beirut or elsewhere.

The works are black and white except for blood-red highlights that seem to symbolise the violence from pro-government forces that saw many injured; some fatally. Among the works’ bold lines are patches of dripping ink and indeterminate dots that evoke the pulsing action of the revolution. The thin rice paper used in October 17, 2021 captures the fragility of the dramatic political uprising that engulfed Lebanon. The materials also tie Beijing to Beirut, and draw connections between social struggles the world over.

Al Kadiri made many drawings in the weeks that followed his return from China. His documentation came to a sudden halt when he was violently beaten by pro-government forces in late 2019, leaving him unable to paint or even leave the house. For now, his series of drawings remain unfinished, much like the Lebanese revolution itself. This exhibition now acts as an archive of a crucial moment in Lebanese history.

“I bumped into Abed Al Kadiri on 23 October 2019, in Downtown Beirut, at a makeshift kitchen offering food to hungry and weary protestors. He was fresh off the plane and had not even bothered going home first, eager to participate in the thawra (revolution). Demonstrations had been going on since 17 October when an ill-advised WhatsApp tax provoked Lebanese from all walks of life, across sectarian and other divisions, to come out and protest against decades of graft, political stasis, wanting infrastructure, and social inequity. For months streets would be flooded across Lebanon with people demanding change and accountability from their incompetent and corrupt government.

This was before hyperinflation devalued the Lebanese Pound with 80% causing people to lose their savings and livelihoods, sending the majority of the Lebanese population into poverty. This was before the whole economy crashed, causing an exodus of those who had the means or possibility to leave. This was before 4 August 2020, when at the port of Beirut one of the largest non-nuclear explosions recorded tore through the city and devasted half of it.

In October 2019 when Al Kadiri hastily cut short his trip to China and returned back home to join the uprising, social dreaming and the possibility for thinking systemic change was still on the horizon. Come September 2021 and most, if not all, of this revolutionary fervour has waned and Lebanon has spiralled into a total collapse. Al Kadiri’s series of drawings October 17, 2019. The Lebanese Revolution is therefore a closed historical document, not only chronicling the events of that specific moment, but also commemorating a time of hopeful collective civic revolt that — for now — will not return. As such the drawings can be seen as a diary of a revolution, and at the same time a lamentation of squandered potential.

With the eyes of today and given Lebanon’s descent into darkness, it is easy to forget the mood of unity and agitated excitement of the first days of the revolution, before militia thugs and security services turned on protestors with excessive force. The artist spent his days at the protests and returned at night to his studio to commit the day’s events to paper. The ink and rice paper he brought with him from China formed the perfect foil for these impressions.

Feverish and brimming with raw emotion, these drawings, influenced by the works on paper he saw in China, are less detailed than his other work, usually thick with oil paint. Rather, these drawings express a furious energy coupled with a sense of anticipatory dread, as seen in the drawing November 6, 2019, which shows a group of people breaching the perimeter of the construction site of the controversial Eden Bay resort planned in Ramlet al-Baida, Beirut’s last public beach. Like many other neoliberal cities in the region, Beirut’s staggering privatisation and corporatisation of public space has lined the pockets of politicians and robbed ordinary Beirutis from their right to the city.

The many urban vistas Al Kadiri has catalogued, are also a demand to reinstate that right. For example, in October 28, 2019 we see hundreds of cars people blocked the roads with to voice their dissent. Another drawing, October 13, 2019 depicts a mass of people moving through the tunnel connecting East with West Beirut with the iconic Burj el-Mur, a gutted landmark from the Civil War (1975-1990) towering over the scene. The word huriyah (freedom) in Arabic is wrapped around what looks like a large X and speculates what is next in store for the Lebanese people; here the spectres of the Civil War and the possibility of rekindled violence are always looming. The tension also resonates in November 3, 2019, which shows demonstrators with Lebanese flags on top of

the iconic bullet-ridden Martyrs’ Monument in the city centre.

In a way the uprising remapped Beirutis relationship to their city: reclaiming it, however furtively, and perhaps traversing it in a way that forged alliances across — since the Civil War —still divided urban districts. It also made them find example in the steadfastness of Lebanon’s second and poorest city, Tripoli, represented in November 2, 2019. The aerial view on Beirut’s seaside corniche in Ein Mreisseh offers a snapshot of the human chain formed on 27 October 2019 with thousands interlocking arms from Tripoli in the North to Tyre in the South; a testimony to how anger and solidarity spilled beyond the capital. Two years onwards, the anger has certainly not dissipated, but the belief that coming out onto the streets might effectuate change, has.”

– Nat Muller is and independent curator and writer specialising in contemporary art from the Middle East. She is currently completing a PhD at Birmingham City University on science fiction in visual practices from the Middle East.

Artists

Image Gallery

Abed Al Kadiri

November 6

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 25, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 29, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

November 2, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 24, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 26, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

180 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 27, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

4 August, 2021

2021

Chinese ink on Chinese Paper

180 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 28, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Abed Al Kadiri

October 31, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Sold

Abed Al Kadiri

November 3, 2019

2019

Chinese Ink on Chinese Rice Paper

175 cm x 95 cm

Subscribe to our newsletter for ongoing updates on our artists and exhibitions